Days after the Centre unveiled its ambitious BioE3 policy, aimed at fostering biotechnology-driven manufacturing in India, the Department of Biotechnology has taken its first steps toward implementing the policy. According to officials and scientists, a major move under consideration is the establishment of enzyme-manufacturing facilities that will support bioethanol production, particularly second-generation (2G) bioethanol. This move marks an essential step in India’s growing focus on biotechnology as a tool for sustainable energy, environment, and economic growth.

The First Enzyme Manufacturing Plant in Manesar, Haryana

One of the first initiatives could see an enzyme-manufacturing plant set up in Manesar, Haryana. This facility would provide a crucial supply of enzymes to proposed 2G bio-ethanol plants in Mathura (Uttar Pradesh), Bhatinda (Punjab), and an existing plant in Panipat, Haryana. These plants are part of a larger strategy under the BioE3 (Biotechnology for Economy, Environment, and Employment) policy, which was recently cleared by the Union Cabinet. This policy envisions the creation of ‘bio-foundries’ – biotechnology-driven hubs that would produce feedstock and catalysts essential for the bioethanol industry.

The Growing Need for Ethanol in India

India’s ethanol demand is on a sharp rise, driven primarily by its fuel-blending goals. The NITI Ayog estimates that by 2025–26, India will need around 13.5 billion litres of ethanol annually. Of this, approximately 10.16 billion litres will be required to meet the government’s E20 mandate, which calls for blending 20% ethanol with petrol.

A sizeable portion of this ethanol will come from 2G bioethanol, which is produced from agricultural residue, such as rice straw, rather than the conventional method of using molasses derived from sugarcane. This method offers a more sustainable approach to ethanol production as it relies on waste products rather than valuable food crops.

The Panipat 2G Ethanol Plant: A Pioneer in Bioethanol Production

In 2022, the Indian Oil Corporation Ltd. (IOCL) inaugurated India’s first 2G ethanol plant in Panipat, Haryana. The facility is designed to process rice stubble—an agricultural waste product that is often burned by farmers in North India, contributing to severe air pollution. Capable of producing up to 100,000 litres of ethanol per day, the Panipat plant has the potential to make a significant dent in India’s ethanol requirements. However, it currently operates at only 30% capacity, requiring around 150,000–200,000 tonnes of rice straw annually, typically harvested during the September-October period.

The Role of Enzymes in Ethanol Production

A critical element in the conversion of rice stubble into ethanol is a cocktail of enzymes that break down the organic material into fermentable sugars. At present, these enzymes are mostly imported, and they represent a major portion of the cost of the 2G ethanol production process. Dr. Ramesh Sonthi, Director of the International Centre for Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology (ICGEB), points out that domestic production of these enzymes could significantly reduce costs.

“We have developed enzymes that are as good, if not better, than the ones currently imported for ethanol production at the Panipat plant,” says Dr. Sonthi. “Our enzymes have proven effective in producing up to 15,000 litres of ethanol, and we are now looking to scale up production.”

Collaboration with Praj Industries and Indigenous Enzyme Development

Praj Industries, a leading biotechnology company based in Maharashtra, holds the technology licensing rights for enzymes sourced from the Danish biotechnology firm Novozymes. These enzymes, along with Praj’s proprietary treatment technology, currently power the Panipat plant’s ethanol refining process.

However, India’s efforts to reduce its reliance on imported enzymes are gaining traction. Praj has partnered with ICGEB, which has developed its own enzyme strains, to evaluate the efficacy of these indigenous enzymes. According to Dr. Shams Yazdani, a senior scientist at ICGEB, these locally developed enzymes have performed just as well as imported alternatives in initial tests.

“We are now working with Praj on techno-economic analysis and plant construction,” Dr. Yazdani explains. “Our goal is to produce at least 20,000 litres of ethanol at Panipat using the ICGEB-Praj processes.”

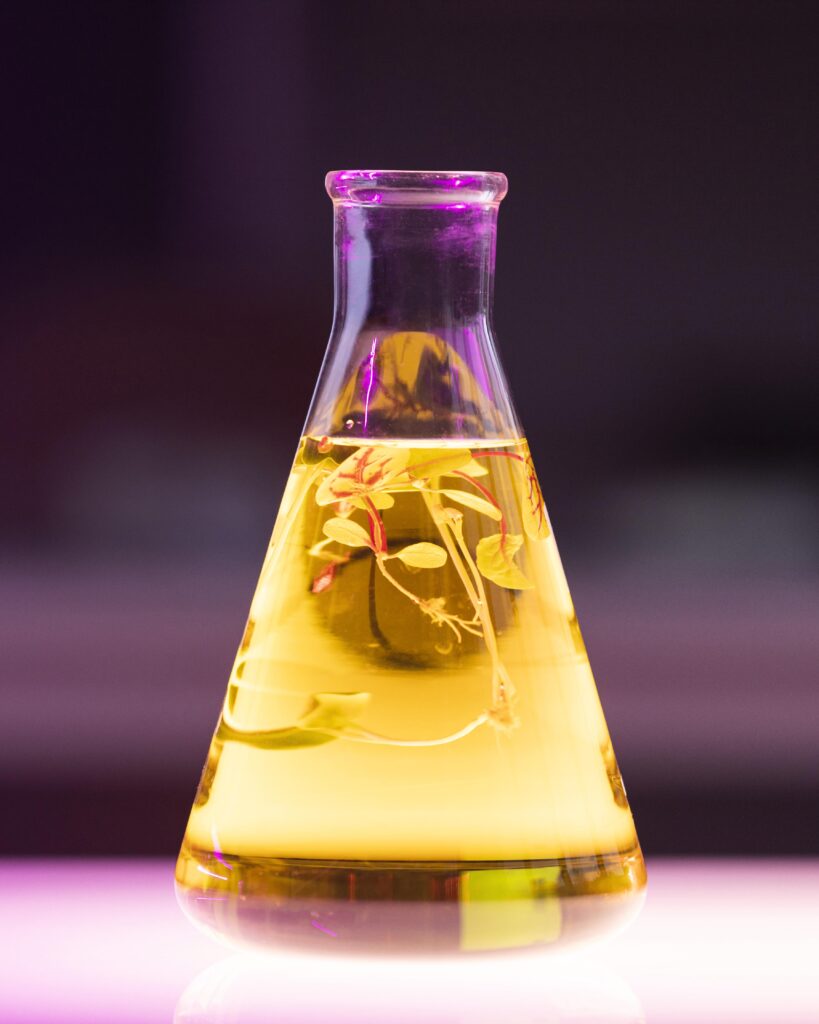

Genetic Engineering and Enzyme Production

The enzymes developed by ICGEB are derived from a fungus belonging to the Penicillium funiculosum family. Through several steps of genetic engineering, the fungus is tweaked to produce enzymes in sufficient quantities that can efficiently break down rice stubble and other organic refuse.

This fungus, which naturally occurs in soil and solid waste, can be cultivated using rice stubble itself. The enzymes it secretes function as powerful hydrolysers that convert biomass into fermentable sugars, which can then be processed into ethanol.

“Our enzyme system is cell-free, meaning the enzymes are readily available to digest the biomass. Once digestion is complete, what you have left is free sugar, which can be used not just for ethanol but also for producing cosmetics and active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs),” says Yazdani.

Reducing Enzyme Costs: A Game Changer for Ethanol Production

If India’s ethanol needs could be met by locally developed enzymes, it would represent a significant cost-saving measure. Dr. Yazdani estimates that switching to domestic enzyme production could cut enzyme procurement costs by about two-thirds. This would help make ethanol production more economically viable, especially as India ramps up its efforts to meet the E20 blending mandate by 2025.

The Environmental and Economic Benefits of 2G Bioethanol

The advantages of 2G bioethanol go beyond cost savings. According to a NITI Ayog report, producing one litre of ethanol requires around 2.3 kg of rice, 2.6 kg of maize, or 50 kg of sugarcane. These are all essential food crops, and using them for fuel competes with food production, while also consuming vast amounts of water.

Relying on agricultural biomass, such as rice stubble, offers a more sustainable solution. Not only does it provide an alternative use for waste products, but it also reduces the harmful practice of stubble burning, which contributes significantly to air pollution in North India.

This year alone, Punjab is expected to produce around 20 million tonnes of rice stubble. While even large plants like the one in Panipat can process only around 200,000 tonnes of stubble annually, scaling up the use of agricultural residue as a feedstock for bioethanol could provide a solution to both the country’s fuel needs and its environmental challenges.

BioE3 Policy: A Step Towards a Greener, Bio-Based Future

The BioE3 policy, approved by the Cabinet last week, aims to place India at the forefront of the global movement away from fossil fuels and towards bio-based alternatives. While the policy does not yet have a dedicated budgetary outlay, it lays the groundwork for a more sustainable future, where biological organisms and biotechnology become the primary sources of energy and consumer products.

“The fossil fuel industry is currently the main source of a wide range of consumer goods, but it also contributes to pollution and plastic waste,” explains Rajesh Gokhale, Secretary of the Department of Biotechnology. “The BioE3 policy aims to change that by leveraging India’s biotech capabilities to drive economic growth, protect the environment, and create new jobs.”

By focusing on bioethanol production and enzyme manufacturing, India is taking significant steps toward achieving its sustainability goals while also reducing its dependence on imported resources. As the BioE3 policy gains momentum, India is positioning itself as a leader in the bio-based economy of the future.

Credit: The Hindu